Songs | Bookbinding | Textiles | Manuscripts | Project Gallery

Paleographic Observations on the Beowulf Manuscript

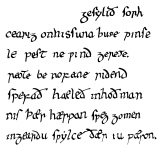

The Beowulf manuscript was originally a small book copied by two different scribes in clear neat hands. Viewing it in person at the British Library, I was struck by how very readable the script is. There are very few abbreviations and the letter forms are well made and consistent. Analyzing a published facsimile (which is unfortunately less clear than the original) I was able to easily identify that the script used in the manuscript is a mixture of Carolingian and Uncial. This is not unusual; many Anglo-Saxon manuscripts have this same mixture of scripts. Although the Beowulf manuscript is a very early example of this blend of scripts being used in a vernacular manuscript. (A manuscript written in the local language rather than Latin.)

History of Carolingian and Uncial in England

Carolingian was the dominant script in the Carolingian Empire from the eighth century through the twelfth. It can be found in Anglo-Latin texts as early as the ninth century, although it does not become predominant for vernacular as well as Latin, until after 1066.

Uncial was developed primarily in Ireland and was used from the 6th through the ninth centuries. It is most well known as the script from the Book of Kells. Developed in Ireland it slowly spread to Northern England where it began to be used in Anglo-Saxon texts.

As the Anglo-Saxons Christianized in the 6th-8th century, they imported Irish monks who brought their scribal tradition with them. Later exposure to the Roman Church's scribal tradition made Carolingian script more popular. The two scripts eventually blended together. King Alfred, a Saxon King who fostered a renaissance of English literature, deliberately retained the distinctive Insular script in all his court documents. After that golden era of Saxon literature, scribes in England still chose to retain some of the more distinctive Uncial letters even though they were predominately writing in a Carolingian script. In particular they tended to keep A, D, E, F, G, H, R, S, C, O, and Y. (The amusing acronym Jane Roberts had for this was def ghras may be coy-- Deaf grass may be coy.)

So the tenth century Beowulf manuscript appears to be an early transitional text from the earlier Uncial script to the newer Carolingian. As one would expect most of the letters in the manuscript are in Carolingian. But a, d, g, and f are remnants from Uncial. The letter s appears in both Carolingian and Uncial-- sometimes even in the same sentence. (I have observed this intermixing of the long S and the short S in texts up through the 19th century.)

Technical Notes on Pens

One of the technical differences between the two hands is that the pen nib is held at a 45-degree angle for Carolingian, while it is held horizontally for Uncial. One of the challenges in transcribing these Beowulf passages was the need to shift the pen angle and then get ink to flow in that new position. This difficulty (according to Pat Lovett) is an artifact of our modern writing tools. A quill pen is less rigid than a metal nib, and so is capable of more smoothly flowing ink at various pen angles. However, she cautioned that an angled writing surface is more critical to allow the ink to "wick" onto the paper. When using a flat surface gravity causes the ink to flow more rapidly, increasing the chance of blobbing.